What motivates you to publish the flashcards?

Elisabela Larrea – When I was researching into the topic, I found that many books on Macanese culture and Patuá were mainly written in Portuguese. I began to wonder how to promote this language further. Many people may think that Patuá is a language solely belongs to the Macanese community, but in fact it is a language of Macau. As a local, I think we all can also learn about the Macanese culture, just like I can learn about the chinese culture of Macau while I am a Macanese. I also hope that people would not feel Patuá is very distant from them. Over the past decade or so, people have been saying that there are only 50 Patuá speakers in the world, but is this figure still accurate? I wanted to do something to bring attention to this language, so I made the first Patuá flashcard.

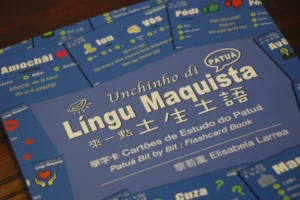

At that time, my mentality was not to ‘teach’ Patuá. Frankly speaking, I have always felt that I am not a linguist nor an expert of Patuá – absolutely not. But I felt that I could do my part to pay attention to and understand the language. At that time, I posted it on my Facebook page as a hobby, but I never thought it would attract attention. I would like to express my special thanks to António Monteiro of the International Institute of Macau. The IIM has always been committed to the preservation and publication of books on the history and culture of Macau. A year ago, António suggested the publications of flashcards, and I immediately agreed to do so.

– The Patuá is more than just a combination of Chinese and Portuguese. How is it related to the creole languages of other places?

E.L. – During the Age of Discovery, the Portuguese have travelled to many places, and some have chosen to settle down there. These inter-ethnic marriages have resulted in the formation of creole languages with its own vocabulary and grammar. Many people who study Patuá mention that the Macanese language is very related to the Kristang language, creole language of Malacca, and that many of the words are very similar. When I went to Singapore for a culture exchange in 2017, it was possible for me to use simple Patuá to converse with another person who speak in simple Kristang. As far as I know, Cape Verde also has its own creole language, but Patuá is the closest to Kristang. The spellings are very different, and they are more Malay, whereas we are more Portuguese, with more Cantonese, so we are different too.

– Some non-locals will also ask you about Patuá?

E.L. – I remember that before the epidemic, a student of linguistics in Shenzhen sent me an email, saying that he had used those flashcards and example sentences to learn how to write Patuá. I think this is quite good, for those who are really interested will conduct in-depth studies when they have the information at hand. There are also people from Japan, Brazil, Singapore, Malaysia and so on, and there are also people from Hong Kong. Some of these emails are from Macanese, but not just Macanese, they are people who are interested in the language, and there are also Portuguese people. A person from Hunan province once told me that he likes Macanese culture and wanted to know more about it. In the past, probably due to the language environment, Macanese used to use Portuguese to explain their culture, and even if they wanted to use Chinese, they might not be able to find the right vocabulary. However, nowadays, more people have different skills to interpret Patuá in new ways, and you can see that there are people who are interested and curious.

– Nowadays, Patuá seems to appear only in the arts, such as literature, lyrics and theatre?

E.L. – I have also written an article before, putting forward a point that Patuá has changed from a language of the family to a language of performance, but in fact, there are different stages. When I started my research, I suggested that it had become a language of performance – not just performing on stage, but also demonstrating one’s cultural identity while off stage. However, in recent years, I feel that Patuá has gradually changed from a language of performance to a language of family. For example, another friend of mine and I use Patuá for simple conversations because we need to practise it, and so the language has returned from performance to life. Of course, it’s unlikely that the language will return to its former popularity. Still, although my mother’s generation didn’t speak Patuá, in recent years as more people are interested in the language, sometimes my mother would also ask me, ‘Is this the right way to say it? She knows many Patuá words. The older generation may not always use Patuá, but they would also want to revive their own language.

Do the vocabulary and grammar of Patuá keep evolving?

E.L. – Language evolves, and so does Cantonese; 100 years ago, there was no television, and when television appears, we need to create new words to represent television. When we create words, we make reference to the conventions of the Macanese language. For example, coração (heart) is coraçám, and when it comes to televisão (television), we use a similar convention to create a new word. Since Patuá is a language of family, a lot of things may revolve around family life, and when we have to talk about something very vague and philosophical, we may have to create some words, but we will try our best to follow the Patuá habit, and we may borrow words from the Portuguese language, and then change them according to the Patuá habit. I think Patuá theatre is a big reason for the creation of words, because it needs to perform modern things, so it has to create some words. Therefore, if a linguistic and social study is to be conducted on Patuá, Adé, the writer, is a very important stage, and the second stage may be the impact of Patuá theatre on the language, but this needs to be studied in depth.

– What results do you hope to achieve by publishing the flashcards?

E.L. – I hope that people will be interested in learning about it, and I also hope that the elders who know Patuá can take the book and teach it to their descendants. I also hope that they can criticise when they see something wrong, because if they do, they can explain and tell more stories to the people around them. I think this book is a “bait” for people to discuss and understand.

– If you had to choose a word or phrase that best represents the Patuá, what would you choose?

E.L. – For a word, I would choose “Amochâi” (darling) because it’s so classic, half in Portuguese and half in Cantonese. “Châi” means “Little”, which has an affectionate feeling in Cantonese, so I always choose Amochâi. If it’s a sentence, I would choose “Macau têm na iou-sa coraçám”, which means “Macau is in my heart”. I think it represents people who like Macau, not just representing the Macanese.